Fo's first important job was with RAI, the State broadcasting corporation, in 1952 at the age of 26. He broadcast a series of grotesque monologues, in a mixture of Italian and Lombard dialect, centering around the figure of Poer nano (Poor git), the poor wretch disregarded by establishment historians. These monologues consisted of an idiosyncratic re-examination of history and literature in the popular culture mode of the world upside-down. So, for example, in the retold version of David and Goliath,the good-natured giant lets himself be killed so that no one could say he took advantage of his opponent's weakness. Recasting the stories of Cain and Abel, Caesar and Brutus, and Othello and Iago, Fo puts on the shoes of the 'bad guys' and overturns the clichés enshrined in the establishment culture.

In a recent reappraisal of Poer nano, Fo has claimed to find the elements o[ a critique of conventional morality in favour of the dispossessed victims of bourgeois historiography. This ideological interpretation of what was originally simple entertainment would not be very convincing were it not for the fact that, despite very high audience ratings RAI interrupted the broadcasting of Poer nano after the eighteenth episode. Clearly Fo had gone beyond the joke and someone had noticed.The importance of this experience for Fo was that it demonstrated the effectiveness of the theatrical formulae which he was to use thereafter .

Meanwhile, success on the radio and in revue brought Fo to the cinema. The Carlo Lizzani film Lo svitato (The Screwball, 1956), with Fo in the title role, was comprehensively slated by the critics. And with reason; but nevertheless the film made the rounds of all the provincial and hinterland cinemas, and introduced Fo's name to the large and undiscriminating public - not yet reached by television - which he was to try and capture twelve years later, in radically different social circumstances and with changed ideological intentions.

So, when Fo set himself up independently in 1959, he had a solid experience of writer-acting and could count on a good degree of popularity. An important contribution to this popularity was made by Franca Rame - married to Fo in 1954 - herself an exceptionally experienced 'daughter of the stage'. Franca Rame deserves more space than we can spare here. Briefly, the development of her stage persona in Fo's theatre parallels the evolution of that theatre. During Fo's bourgeois period, the beautiful Rame, a versatile actress with great comic talent, played the dumb blonde whose magnetic sex-appeal was exploited to the full with exiguous costumes and saucy poses. In the years of the economic miracle she became the incarnation of the wildest erotic fantasies of the typically repressed, mother-smothered Catholic man in the street. Indeed it is hard to tell whether the audiences were more attracted by Fo's daring jokes and astounding performances or by Rame's seductive presence on the stage. Whatever the case, this formula - one consumed with particular avidity by audiences of the 1960s - brought Fo and Rame considerable success, televised and live. The disingenuous exploitation of the dumb blonde ended in 1968 when Rame began to explore new personas within the context of the feminist movement. This process culminated in 1978 with her Tutto casa, letto e chiesa (Just home, Bed and Church, adapted in English as Female Parts: One Woman Plays, 1981), a series of monologues on the condition of women in contemporary Italian society.

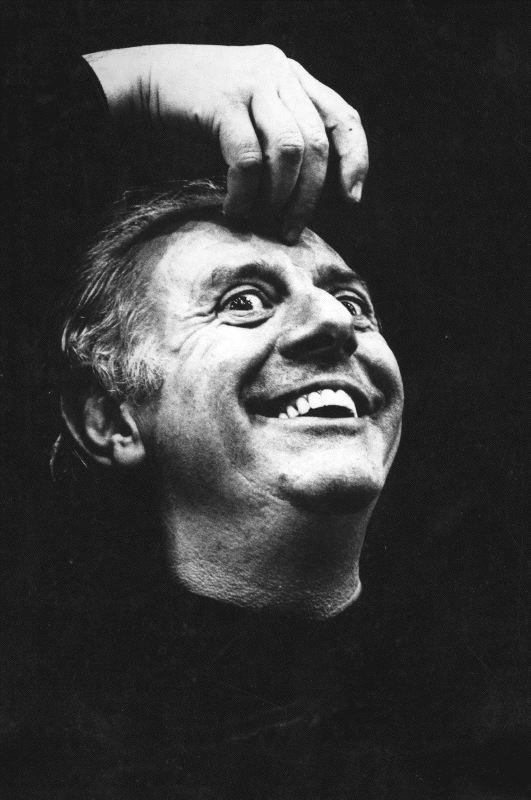

In September 1959, the newly-formed 'Compagnia teatrale Dario Fo - Franca Rame' gave its first performance of Gli arcangeli non giocano a flipper (Archangels Don't play pinball ) at the Odeon in Milan. This was followed at yearly intervals by, Aveva due pistole con gli occhi bianchi e neri (He had Two Guns with Black and White Eyes) and Chi ruba un piede è fortunato in amore (He who Steals a Foot is lucky in Love). All three are well-produced and basically conventional light comedies. Compared with the brief, explosive absurdity of the Poer nano monologues, these comedies are wittier and more inventive, but also more drawn-out. The 'world-upside-down' formula is taken to its limits in a frenetic succession of situations, parodies and ridiculous double entendres generated by rapid-fire verbal association. Fo's protean personality dominates these pyrotechnic performances - by turns actor, mime, dancer, clown and maschera, he can raise a laugh from nowhere, in an apparently easy and spontaneous recitation that is however pervaded with disturbing satirical allusions.

Clearly the tension between 'theatrical animal' and moral commitment is not yet posed in a disciplined and conscious way. Even the satire, usually a minor element in these comedies, arises not so much from a particular programme of criticism, as from Fo's own effervescent love of life and theatre, his desire for recognition and success. The comic structure is still conventional, so too the content, despite a certain daring suited to the liberal audiences in the capital of the on-going economic miracle. The reality of the situation was, however, that despite his vitriolic darts against national scandals, corruption and the hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie, such theatre could only play the establishment's game. This was because Fo was speaking to a cultured bourgeois audience in the register of bourgeois theatre. To present corruption in the highest places in farcical terms could legitimize corruption in the ordinary bourgeois citizens who were his audience - far from feeling threatened they felt absolved.

It was in these conditions that in 1962 Fo and Rame were invited to produce, direct and present Canzonissima, the most popular television programme of the day. This was the ultimate accolade from the Italian show-business world, and Fo had achieved it within only ten years. It was his triumph for the present and an assurance of future success. Canzonissima was broadcast every Saturday between October and January each year at peak-viewing times. Linked with a national lottery it offered a selection of new pop songs (in the old Italian sentimental style) from which the public had to choose the most 'canzone', the 'canzonissima'. And the invitation to Fo came at a moment when. with the cautious 'opening' of the government to the Socialist Party,even some DC fiefs, like RAI-TV, seemed prepared to give space to opinions and forms of expression which were not directly controlled from the centre.

It was against this background that Fo appeared on television, with a fairly broadminded programme of songs, satirical sketches, sallies aimed at one or another prominent personage, and comic renderings of typical (but not stereotyped) Italian situations. The mixture was intended to stimulate thoughtful viewers to question the cultural value of this kind of entertainment. The first programme opened, according to a well-tested Fo formula, with a song whose words were slightly unusual:

In a recent reappraisal of Poer nano, Fo has claimed to find the elements o[ a critique of conventional morality in favour of the dispossessed victims of bourgeois historiography. This ideological interpretation of what was originally simple entertainment would not be very convincing were it not for the fact that, despite very high audience ratings RAI interrupted the broadcasting of Poer nano after the eighteenth episode. Clearly Fo had gone beyond the joke and someone had noticed.The importance of this experience for Fo was that it demonstrated the effectiveness of the theatrical formulae which he was to use thereafter .

Meanwhile, success on the radio and in revue brought Fo to the cinema. The Carlo Lizzani film Lo svitato (The Screwball, 1956), with Fo in the title role, was comprehensively slated by the critics. And with reason; but nevertheless the film made the rounds of all the provincial and hinterland cinemas, and introduced Fo's name to the large and undiscriminating public - not yet reached by television - which he was to try and capture twelve years later, in radically different social circumstances and with changed ideological intentions.

So, when Fo set himself up independently in 1959, he had a solid experience of writer-acting and could count on a good degree of popularity. An important contribution to this popularity was made by Franca Rame - married to Fo in 1954 - herself an exceptionally experienced 'daughter of the stage'. Franca Rame deserves more space than we can spare here. Briefly, the development of her stage persona in Fo's theatre parallels the evolution of that theatre. During Fo's bourgeois period, the beautiful Rame, a versatile actress with great comic talent, played the dumb blonde whose magnetic sex-appeal was exploited to the full with exiguous costumes and saucy poses. In the years of the economic miracle she became the incarnation of the wildest erotic fantasies of the typically repressed, mother-smothered Catholic man in the street. Indeed it is hard to tell whether the audiences were more attracted by Fo's daring jokes and astounding performances or by Rame's seductive presence on the stage. Whatever the case, this formula - one consumed with particular avidity by audiences of the 1960s - brought Fo and Rame considerable success, televised and live. The disingenuous exploitation of the dumb blonde ended in 1968 when Rame began to explore new personas within the context of the feminist movement. This process culminated in 1978 with her Tutto casa, letto e chiesa (Just home, Bed and Church, adapted in English as Female Parts: One Woman Plays, 1981), a series of monologues on the condition of women in contemporary Italian society.

In September 1959, the newly-formed 'Compagnia teatrale Dario Fo - Franca Rame' gave its first performance of Gli arcangeli non giocano a flipper (Archangels Don't play pinball ) at the Odeon in Milan. This was followed at yearly intervals by, Aveva due pistole con gli occhi bianchi e neri (He had Two Guns with Black and White Eyes) and Chi ruba un piede è fortunato in amore (He who Steals a Foot is lucky in Love). All three are well-produced and basically conventional light comedies. Compared with the brief, explosive absurdity of the Poer nano monologues, these comedies are wittier and more inventive, but also more drawn-out. The 'world-upside-down' formula is taken to its limits in a frenetic succession of situations, parodies and ridiculous double entendres generated by rapid-fire verbal association. Fo's protean personality dominates these pyrotechnic performances - by turns actor, mime, dancer, clown and maschera, he can raise a laugh from nowhere, in an apparently easy and spontaneous recitation that is however pervaded with disturbing satirical allusions.

Clearly the tension between 'theatrical animal' and moral commitment is not yet posed in a disciplined and conscious way. Even the satire, usually a minor element in these comedies, arises not so much from a particular programme of criticism, as from Fo's own effervescent love of life and theatre, his desire for recognition and success. The comic structure is still conventional, so too the content, despite a certain daring suited to the liberal audiences in the capital of the on-going economic miracle. The reality of the situation was, however, that despite his vitriolic darts against national scandals, corruption and the hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie, such theatre could only play the establishment's game. This was because Fo was speaking to a cultured bourgeois audience in the register of bourgeois theatre. To present corruption in the highest places in farcical terms could legitimize corruption in the ordinary bourgeois citizens who were his audience - far from feeling threatened they felt absolved.

It was in these conditions that in 1962 Fo and Rame were invited to produce, direct and present Canzonissima, the most popular television programme of the day. This was the ultimate accolade from the Italian show-business world, and Fo had achieved it within only ten years. It was his triumph for the present and an assurance of future success. Canzonissima was broadcast every Saturday between October and January each year at peak-viewing times. Linked with a national lottery it offered a selection of new pop songs (in the old Italian sentimental style) from which the public had to choose the most 'canzone', the 'canzonissima'. And the invitation to Fo came at a moment when. with the cautious 'opening' of the government to the Socialist Party,even some DC fiefs, like RAI-TV, seemed prepared to give space to opinions and forms of expression which were not directly controlled from the centre.

It was against this background that Fo appeared on television, with a fairly broadminded programme of songs, satirical sketches, sallies aimed at one or another prominent personage, and comic renderings of typical (but not stereotyped) Italian situations. The mixture was intended to stimulate thoughtful viewers to question the cultural value of this kind of entertainment. The first programme opened, according to a well-tested Fo formula, with a song whose words were slightly unusual:

People of the miracle, of the economic miracle, oh magnificent people, champions of freedom. Free to move, free to sing, to sing and to counter-sing, from the chest and in falsetto. Let's sing, let's sing, let's not think in case we argue, let's sing. Let's make the orphans sing, and the widows who weep and the workers on strike, let's get them all to sing. . .

This was followed by irreverent and anticonformist sketches parodying other programmes. satirising the police, the bureaucracy, and in one grotesque and openly allusive instance, the worker who toadies to the boss. So keen was he not to stop the mincing machine, that he had to take home the 150 tins containing his aunt who came to visit him in the factory and ended up in the cogs of industry.

Howls of indignation went up from the conservative press, and even in parliament. Heavy censorship was imposed on Fo's texts and he was forced to resign after the seventh episode. Clearly, while the country was ripe for Fo's invigorating anti-conformism, its institutions were still living in the times of De Gasperi. The only victors of this furore were Fo's enhanced reputation and the increased sales of televisions. But the Canzonissima experience was crucial for Fo, burdened as he was with censorship and at Ioggerheads with ETI (the Italian Theatre council). It revealed the truly conservative character of the apparent leftward opening in the DC - like Canzonissima it was a manoeuvre to soothe the opposition into the system. It helped him to identify his resolve not to compromise with the dominant conformity. The Fo who emerges is more aggressive, more aware of his strengths and of the contradictions inherent in his cultural environment, more demanding too about the forms and contents of his own shows. His success would now serve a more rigorous and systematic political satire.

Over the next three years Fo produced three new comedies, first shown, as usual, at the Odeon in Milan and then doing the ETI circuit: Isabella, tre caravelle e un cacciaballe (Isabel, three Caravels and a Bamboozler, 1963), Settimo, ruba un po' meno (Seventh, Steal a Bit Less, 1964) and La colpa è sempre del diavolo (It's Always the Devil's Fault, 1965). Compared with his previous work, this group of plays was characterised by more complex and interwoven structures, without digressions from the main plot, and an attempt to bring social and political satire to the forefront, though without in any way slowing the pace or diminishing the entertainment value. Fo managed to combine moral fervour and dramatic interest, depicting raw and disturbing actuality with the limited possibilities of the farcical. In short he succeeded in harnessing the instincts of the 'theatrical anima| without compromising his mission as anti-conformist intellectual.

Isabella is a grotesque and symbolic version of the story of Christopher Columbus in which he flirts with power, is corrupted and ends up a poor wretch in dire straits. This plot is an obvious metaphor for the condition of the intellectual in Italy under the centre-left regime. Some technical devices new to Fo's theatre are introduced, notably the theatre-within-a-theatre. The play is also notable for the body of research and historical documentation on which it draws. Where this procedure differs from that of Poer nano is that here the past is systematically desecrated in accordance with an ideological interpretation of the present.

The last chorus of Isabella closes thus: 'The real smart alec is the straight guy, not the opportunist. It's the guy who at all costs stays always and only on the side of the poor sods, of the fair men.' This moralising conclusion is a bridge towards the following show, Settimo, certainly the best of Fo's bourgeois period and one of his finest works. The plot is too complex to summarize here. Suffice it to say, each scene aims to unmask and pillory some aspect of endemic national corruption. At the end the exhilirating crescendo is brusquely interrupted by some worthy political personage - a genuine deus ex machina - who silences everything, thus brutally frustrating the audience's desire to see justice done if only on the stage, and thereby entrusting it with the responsibility for seeing justice done off-stage. The settings - a cemetery, and a bank/convent/lunatic asylum - are a transparent allegory of alienated and 'miraculous' Italy, and the alliances of its ruling classes. For the first time Fo directly confronts the reality of Italy and analyzes it in a grotesque register. A bunch of grave-diggers from the cemetery - which is about to be cleared to make way for a kolossal illegal building project - watch an off-stage clash between police and strikers, some of whom are killed. For the first time the Italian public is being exposed to scenes like this. The song of the lunatics is hardly less provocative:

Howls of indignation went up from the conservative press, and even in parliament. Heavy censorship was imposed on Fo's texts and he was forced to resign after the seventh episode. Clearly, while the country was ripe for Fo's invigorating anti-conformism, its institutions were still living in the times of De Gasperi. The only victors of this furore were Fo's enhanced reputation and the increased sales of televisions. But the Canzonissima experience was crucial for Fo, burdened as he was with censorship and at Ioggerheads with ETI (the Italian Theatre council). It revealed the truly conservative character of the apparent leftward opening in the DC - like Canzonissima it was a manoeuvre to soothe the opposition into the system. It helped him to identify his resolve not to compromise with the dominant conformity. The Fo who emerges is more aggressive, more aware of his strengths and of the contradictions inherent in his cultural environment, more demanding too about the forms and contents of his own shows. His success would now serve a more rigorous and systematic political satire.

Over the next three years Fo produced three new comedies, first shown, as usual, at the Odeon in Milan and then doing the ETI circuit: Isabella, tre caravelle e un cacciaballe (Isabel, three Caravels and a Bamboozler, 1963), Settimo, ruba un po' meno (Seventh, Steal a Bit Less, 1964) and La colpa è sempre del diavolo (It's Always the Devil's Fault, 1965). Compared with his previous work, this group of plays was characterised by more complex and interwoven structures, without digressions from the main plot, and an attempt to bring social and political satire to the forefront, though without in any way slowing the pace or diminishing the entertainment value. Fo managed to combine moral fervour and dramatic interest, depicting raw and disturbing actuality with the limited possibilities of the farcical. In short he succeeded in harnessing the instincts of the 'theatrical anima| without compromising his mission as anti-conformist intellectual.

Isabella is a grotesque and symbolic version of the story of Christopher Columbus in which he flirts with power, is corrupted and ends up a poor wretch in dire straits. This plot is an obvious metaphor for the condition of the intellectual in Italy under the centre-left regime. Some technical devices new to Fo's theatre are introduced, notably the theatre-within-a-theatre. The play is also notable for the body of research and historical documentation on which it draws. Where this procedure differs from that of Poer nano is that here the past is systematically desecrated in accordance with an ideological interpretation of the present.

The last chorus of Isabella closes thus: 'The real smart alec is the straight guy, not the opportunist. It's the guy who at all costs stays always and only on the side of the poor sods, of the fair men.' This moralising conclusion is a bridge towards the following show, Settimo, certainly the best of Fo's bourgeois period and one of his finest works. The plot is too complex to summarize here. Suffice it to say, each scene aims to unmask and pillory some aspect of endemic national corruption. At the end the exhilirating crescendo is brusquely interrupted by some worthy political personage - a genuine deus ex machina - who silences everything, thus brutally frustrating the audience's desire to see justice done if only on the stage, and thereby entrusting it with the responsibility for seeing justice done off-stage. The settings - a cemetery, and a bank/convent/lunatic asylum - are a transparent allegory of alienated and 'miraculous' Italy, and the alliances of its ruling classes. For the first time Fo directly confronts the reality of Italy and analyzes it in a grotesque register. A bunch of grave-diggers from the cemetery - which is about to be cleared to make way for a kolossal illegal building project - watch an off-stage clash between police and strikers, some of whom are killed. For the first time the Italian public is being exposed to scenes like this. The song of the lunatics is hardly less provocative:

Nearly once every day they give us electric shock treatment because we're psychopathic, not to mention neurotic, and being endocephalic we're outside society . . . But at the last elections the nuns helped us to vote, to vote with the little cross, holding our hands, singing us a story, and all for the glory of this civilisation . . . And thanks to the well-known method of conditioning in this convent, we're more normal now . . . We're still psychopathic, tainted endocephalics, but we know the rules of conventional thinking: he who wants things to stay the way they are is wise, and he who complains about the little he hasn't got is mad.

A novelty in this show was the creation o[ a substantial character - the gravedigger Enea - around whom the whole action revolves freely. Enea is more than a variation on the sterotype - dear to comedy and to Fo - of the simpleton. She is a kind of Fellinian Cabiria, innocent and unsmirched by the corruption around her; a character whom the author looks upon with ill-concealed tenderness, capable of eliciting the uncharacteristic lyricism which was to reappear in the later 'committed' works. The most delicate and magical moments occur when Enea meets other creatures, imagined and real, from an honest, pre-industrial world; the whore who gives Enea the street-woman's outfit she had so long wanted; her dead father, still drunk even as a ghost; the cherubim who speak in grammelot, described by Fo as 'a series of sounds without apparent sense, but so onomatopoeic and allusive in their cadences and inflections as to allow their sense to be intuited'. At the end she is the only one to save herself from the rampant alienation of bourgeois society. But the force of this character is completely moral, rather than political. There is some way to go before we reach class-consciousness.

The next farce, La colpa è sempre del diavolo, is almost too rich in inventiveness and somewhat undeveloped satirical sallies. At the politico-historical kernel of the play is the struggle between the Holy Roman Emperor and the Cathars, the communitarian and evangelical sect wiped out for heresy in the late thirteenth century. Here too, the allegory is obvious. The Cathar communards stand for the Italian communists, the Imperial forces represent the USA which, at the time, was stepping up its commitment in Vietnam. An interesting pointer to the later Fo is his attempt here to disinter authentically revolutionary episodes from the history of popular culture, especially those involving pre-Reformation evangelical religion, which challenges the corrupt and reactionary orthodoxy from an, as it were, left-wing point of view.

It was works like this which highlighted the absence of a coherent ideology uniting Fo's theatre and its audiences. Otherwise, what was the point of recreating forgotten popular uprisings for the bourgeois audiences in the Milan Odeon? In a vain attempt to fill this ideological void Fo was pushing the ambiguities of farce and theatricality to their limits. But he was knocking on an open door. While his farces were getting more and more daring, his public had become broader-minded. In industrialized Italy the middle class (and no other class went to the theatre) was as liberal and permissive as any of its European counterparts, and it needed more than a Fo farce to shock it. Fo realized that he had become 'court jester' to the bourgeosie. On top of this, there was a ferment of fresh ideas. The Living Theatre had

arrived and new dramatic forms were being discussed especially in youth and left-wing intellectual circles. The wind of change reached even that pop music business which Fo had castigated so ferociously for its ability to take genuinely popular art forms, make them banal and use them against the masses. Something of this sentiment inspired the 'Nuovo Canzoniere Italiano', a group of young, left-wing musicians and musicologists who were beginning to exhume - with scrupulous historical and philological rigour - the inheritance of authentically popular songs, old and new, which still preserved the pristine intensity of the people's rage against the injustice and greed of its rulers. Fo and the 'Nuovo Canzoniere' group collaborated - not without dissensions - on a new show, Ci ragiono e canto (l'll Think and Sing about It, 1967). If the popular songs here lose a degree of philological purity, there is a more than adequate compensation in terms of dramatic, hence didactic, intensity. Fo's idea had been to recreate the context of gestures from which the songs had emerged, the gestures of the workers in the fields, on the rivers, in the factories.

These were not the only avenues Fo was investigating at this time. In September 1967 he offered his middle-class audience something quite different, La signora è da buttare (Madam is Disposable), a free-wheeling satire of capitalist America consisting of a series of political vignettes staged by clowns and acrobats in a vertiginous whirl of witticisms, somersaults, jokes and acrobatics. The audience was perplexed by the unusual show and by the vitriolic attack on America. The police, for once without a definitive text with which to indict Fo, were alarmed. Eventually Fo was threatened with arrest and cautioned for jokes 'offensive to the head of a foreign state' (Lyndon B. Johnson). It was the end of Fo's bourgeois era. At the peak of his professional success Fo decided to leave ETI, to leave the official theatre circuit and its guaranteed full houses, and instead to put his theatre to work for the people. In order not to be the court jester of the bourgeoisie he was prepared to start all over again.

In 1968 Dario Fo and Franca Rame set up the 'Associazione Nuova Scena' with the declared intention of putting their skills to work for the revolutionary forces, not to reform the bourgeois state with opportunist politics, but to encourage the growth of a genuine revolutionary process which would bring the working class to power' (Binni 1977 ,46). This new association abolished the hierarchical power-structures typical of conventional theatre companies. It also proposed to create an alternative theatre circuit. -This would lean heavily on the resources of the Italian Recreational Culture Association (ARCI), which was the cultural wing of the Italian Communist Party, and its network of co-operatives and case del popolo (working people's recreational clubs). The new audiences w'ere to be drawn from the working classes, the mass of workers and their families who had never been in a theatre. And one of the new circuit's advantages was that since it consisted of private clubs it lay outside the jurisdiction of the censor, and police interference.

It was no coincidence then that 1968 saw in Fo's work a new quality which had been previously conspicuous by its absence. There was now a mature political awareness. The themes he chose could be analyzed in an ideologically coherent and committed fashion. To put it simplistically, Fo based his ideas on the concept of the class-struggle (and we should recognize here a degree of influence from Franca Rame, who had joined the PCI in 1967 ). Henceforth all his works were [o revolve about this basic premise. Now the challenge was to bring all the resources of his theatre to bear on the political and cultural issues of the day. This meant tackling them together with the audience - another novel

element - and sweeping away the last vestiges of the 'fourth wall' by means of which the theatre had traditionally been able to neutralize cathartically the most disturbing events on the stage. Fo concentrated more on the audience's reactions - indeed he positively invited its participation. Ho also instituted the 'third act' a period of discussion which followed the show. By reconstituting traditional street-theatre in the light of his newly forged ideology, Fo nudged the spectators out of their passive voyeurism and made them participate in the production as well as the performance of the show. Technically speaking that meant an increasing recourse to improvisation, pantomime and gesture - Fo's natural forte. But paradoxically, this new praxis required of the actor-author an even greater intelligence and mastery of the medium, if the message was not to be submerged in banalities. While it was enough just to entertain, or at the most, provoke a middle-class audience, when dealing with a proletarian audience the need to raise laughs could not be allowed to obscure the over-riding didactic requirement. Gesture and pantomime could no longer be gratuitous,

but had to be invested, à la Brecht, with social meaning.

Undoubtedly the most committed product of this most intense phase in Fo's career, and probably his most original work altogether is Mistero Buffo (Comic Mystery Play), first put on at the Cusano Milanino casa del popolo in October 1969, and then performed all over Italy and abroad in modified and expanded versions. It is a collage of mediaeval texts, some original, some altered, some even made up by Fo on the basis of a variety o[ historical inspirations. These texts are presented critically, then interpreted, by Fo who - in a dark sweat-shirt and trousers - remains alone on the otherwise empty stage for the entire show. The interest in research, which had led Fo to excavate mediaeval history to find material for his theatre, comes to its finest fruition in Mistero Buffo. More recently Fo had been very impressed with the experience of Ci ragiono e canto, re-done in 1968 in a politically revamped version. Shows like these gratified Fo's 'court jester' vocation, but allowed him to put his all-round acting skills to serve his ideological convictions rather than to entertain the bourgeoisie. For Fo, the jester was the incarnation o{ the creativity of popular culture at a time when it was still distinct from, even antagonistic to, the culture of the aristocracy.

The next farce, La colpa è sempre del diavolo, is almost too rich in inventiveness and somewhat undeveloped satirical sallies. At the politico-historical kernel of the play is the struggle between the Holy Roman Emperor and the Cathars, the communitarian and evangelical sect wiped out for heresy in the late thirteenth century. Here too, the allegory is obvious. The Cathar communards stand for the Italian communists, the Imperial forces represent the USA which, at the time, was stepping up its commitment in Vietnam. An interesting pointer to the later Fo is his attempt here to disinter authentically revolutionary episodes from the history of popular culture, especially those involving pre-Reformation evangelical religion, which challenges the corrupt and reactionary orthodoxy from an, as it were, left-wing point of view.

It was works like this which highlighted the absence of a coherent ideology uniting Fo's theatre and its audiences. Otherwise, what was the point of recreating forgotten popular uprisings for the bourgeois audiences in the Milan Odeon? In a vain attempt to fill this ideological void Fo was pushing the ambiguities of farce and theatricality to their limits. But he was knocking on an open door. While his farces were getting more and more daring, his public had become broader-minded. In industrialized Italy the middle class (and no other class went to the theatre) was as liberal and permissive as any of its European counterparts, and it needed more than a Fo farce to shock it. Fo realized that he had become 'court jester' to the bourgeosie. On top of this, there was a ferment of fresh ideas. The Living Theatre had

arrived and new dramatic forms were being discussed especially in youth and left-wing intellectual circles. The wind of change reached even that pop music business which Fo had castigated so ferociously for its ability to take genuinely popular art forms, make them banal and use them against the masses. Something of this sentiment inspired the 'Nuovo Canzoniere Italiano', a group of young, left-wing musicians and musicologists who were beginning to exhume - with scrupulous historical and philological rigour - the inheritance of authentically popular songs, old and new, which still preserved the pristine intensity of the people's rage against the injustice and greed of its rulers. Fo and the 'Nuovo Canzoniere' group collaborated - not without dissensions - on a new show, Ci ragiono e canto (l'll Think and Sing about It, 1967). If the popular songs here lose a degree of philological purity, there is a more than adequate compensation in terms of dramatic, hence didactic, intensity. Fo's idea had been to recreate the context of gestures from which the songs had emerged, the gestures of the workers in the fields, on the rivers, in the factories.

These were not the only avenues Fo was investigating at this time. In September 1967 he offered his middle-class audience something quite different, La signora è da buttare (Madam is Disposable), a free-wheeling satire of capitalist America consisting of a series of political vignettes staged by clowns and acrobats in a vertiginous whirl of witticisms, somersaults, jokes and acrobatics. The audience was perplexed by the unusual show and by the vitriolic attack on America. The police, for once without a definitive text with which to indict Fo, were alarmed. Eventually Fo was threatened with arrest and cautioned for jokes 'offensive to the head of a foreign state' (Lyndon B. Johnson). It was the end of Fo's bourgeois era. At the peak of his professional success Fo decided to leave ETI, to leave the official theatre circuit and its guaranteed full houses, and instead to put his theatre to work for the people. In order not to be the court jester of the bourgeoisie he was prepared to start all over again.

In 1968 Dario Fo and Franca Rame set up the 'Associazione Nuova Scena' with the declared intention of putting their skills to work for the revolutionary forces, not to reform the bourgeois state with opportunist politics, but to encourage the growth of a genuine revolutionary process which would bring the working class to power' (Binni 1977 ,46). This new association abolished the hierarchical power-structures typical of conventional theatre companies. It also proposed to create an alternative theatre circuit. -This would lean heavily on the resources of the Italian Recreational Culture Association (ARCI), which was the cultural wing of the Italian Communist Party, and its network of co-operatives and case del popolo (working people's recreational clubs). The new audiences w'ere to be drawn from the working classes, the mass of workers and their families who had never been in a theatre. And one of the new circuit's advantages was that since it consisted of private clubs it lay outside the jurisdiction of the censor, and police interference.

It was no coincidence then that 1968 saw in Fo's work a new quality which had been previously conspicuous by its absence. There was now a mature political awareness. The themes he chose could be analyzed in an ideologically coherent and committed fashion. To put it simplistically, Fo based his ideas on the concept of the class-struggle (and we should recognize here a degree of influence from Franca Rame, who had joined the PCI in 1967 ). Henceforth all his works were [o revolve about this basic premise. Now the challenge was to bring all the resources of his theatre to bear on the political and cultural issues of the day. This meant tackling them together with the audience - another novel

element - and sweeping away the last vestiges of the 'fourth wall' by means of which the theatre had traditionally been able to neutralize cathartically the most disturbing events on the stage. Fo concentrated more on the audience's reactions - indeed he positively invited its participation. Ho also instituted the 'third act' a period of discussion which followed the show. By reconstituting traditional street-theatre in the light of his newly forged ideology, Fo nudged the spectators out of their passive voyeurism and made them participate in the production as well as the performance of the show. Technically speaking that meant an increasing recourse to improvisation, pantomime and gesture - Fo's natural forte. But paradoxically, this new praxis required of the actor-author an even greater intelligence and mastery of the medium, if the message was not to be submerged in banalities. While it was enough just to entertain, or at the most, provoke a middle-class audience, when dealing with a proletarian audience the need to raise laughs could not be allowed to obscure the over-riding didactic requirement. Gesture and pantomime could no longer be gratuitous,

but had to be invested, à la Brecht, with social meaning.

Undoubtedly the most committed product of this most intense phase in Fo's career, and probably his most original work altogether is Mistero Buffo (Comic Mystery Play), first put on at the Cusano Milanino casa del popolo in October 1969, and then performed all over Italy and abroad in modified and expanded versions. It is a collage of mediaeval texts, some original, some altered, some even made up by Fo on the basis of a variety o[ historical inspirations. These texts are presented critically, then interpreted, by Fo who - in a dark sweat-shirt and trousers - remains alone on the otherwise empty stage for the entire show. The interest in research, which had led Fo to excavate mediaeval history to find material for his theatre, comes to its finest fruition in Mistero Buffo. More recently Fo had been very impressed with the experience of Ci ragiono e canto, re-done in 1968 in a politically revamped version. Shows like these gratified Fo's 'court jester' vocation, but allowed him to put his all-round acting skills to serve his ideological convictions rather than to entertain the bourgeoisie. For Fo, the jester was the incarnation o{ the creativity of popular culture at a time when it was still distinct from, even antagonistic to, the culture of the aristocracy.

Since the tenth century - Fo maintains - the jester has gone from town to town reciting his clowneries, grotesque tirades against the authorities. Even a reactionary historian like Ludovico Antonio Muratori admits that the jester came from the masses, and that it was their rage he was giving back to them through the medium of the grotesque. For the masses, the theatre has always been the principal means of communication, of provocation and agitation. The theatre was the spoken and dramatized newspaper of the people. (Valentini 1977 , 124)

So Mistero buffo was not an operation of archaeological recovery (not an unknown phenomenon in the cinemas and theatres of the sixties), but an attempt to restore to the figure of the jester the actuality and significance he once enjoyed as spokesman for a pristine popular culture, not as yet contaminated and perverted by the cultural colonialism of bourgeois society. The aim of this operation was to give the contemporary worker back his history, his identity, and the dignity of his world-view. Only on this basis, Fo thought, could a new future be founded. There is here an obvious appeal to Gramsci, often quoted by Fo:

To know oneself means to be oneself , to be master of oneself , to individuate oneself , to emerge from a state of chaos, to exist as an element of order - but of one's own order and adherence to an ideal. This cannot be achieved without knowing others, their history, the sequence of efforts they have made to become what they are, to create the civilization they have created, and which we seek to replace with our own. (Gramsci 1972,25)

In becoming historian and court jester to the people, in trying to show the masses the identity, priority and continuity of their culture, Fo adopted an enormous variety of materials. They range from standard school texts such as the thirteenth-century Contrasto by Ciullo d'Alcamo, relieved of its conventional bourgeois-idealistic overlay by means of a sociological analysis, to original drafts (canovacci) like The Morality of the Blind Man and the Cripple by Andrea della Vigna and The Birth of the Jester or The Birth of the Villein attributed to the jester Matazone da Caligano. There

are texts reconstituted entirely out of suggestions found in ancient chronicles, like the story of Boniface VIII, or taken from the Gospels, like The Wedding at Cana and The Raising of Lazarus. The protagonists of these pieces are always the oppressed - the villein, the jester, even Christ - struggling against the arrogance of power. There is also the heretic seen as revolutionary - establishing alternative communities and Iiving his faith as a social as well as a spiritual revolution, until he is exterminated. Using the formulae of the commedia dell'arte, each story juxaposes the two characteristic themes of popular culture: on one hand the gross realities of physical life, and on the other the primitive popular spirituality and its perennial obsession with social justice. On stage Fo breathes life into this mass of material using a specially developed Lombardo-Venetian idiolect. Its low register and archaic flavour contrast with the literary language of bourgeois theatre and with the insinuatingly paternalistic use of dialectal forms, especially Roman, much encouraged by the mass media. In any case the meaningfulness of the spoken word counts far less than that of gesture, which Fo's performances invest with an all-pervasive power of suggestion. Grammelot and pantomime become increasingly the principal media of communication with the public.

How does Fo prevent his extraordinary talent for mime from becoming a dazzling end in itself? How does he prevent the political message from being relegated to the background? Mistero buffo operates in two registers. One is that of contemporary reality, which Fo alludes to in his commentary, in Italian, on slides showing his mediaeval characters. The second register - his Lombardo-Venetian 'dialect' - is used for the actual stories. Fo's aim is to exploit his virtuoso ability to pass from one register to another - to interrupt the performance to respond to the audience or to discuss some contemporary issue and then to slip imperceptibly back into the recitation. Thus he hopes to guide his audience by acting as a spectator of his own creations. By estranging himself from his dramatic selves he sets an example. But this chameleon ability to shift from past to present, from register to register, becomes itself a spectacle. The danger is then that the magical attraction of his solitary presence on the stage distracts the spectators from the lesson Fo wishes to impart. It is as if for dramatic theatre he substitutes epic theatre and ends up producing a variety of the bourgeois theatre that he has repudiated. To be sure, Brechtian theory proposes to avoid the danger of catharsis by employing, among other things, the grotesque register, but the very foundations of the production of popular culture had changed irreversibly by the 1960s and 1970s, and it is not impertinent, I think, to ask whether this use of the grotesque in the theatrical praxis of the time does not lead to a trivialization of content. We will come back to this later. For the moment it is enough to suggest that there was something counter-productive in Fo's efforts, partly because he was a victim of his own myth, partly because his audiences were neither those of Brecht nor those of the piazzas of mediaeval Italy.

Fo put together two other productions in this period. Legami pure che tanto io spacco tutto lo stesso (Tie Me Down as Much as You Like, I'll Still Smash Everything Just the Same) consists of two one-act plays on the theme of the exploitation of the workers. The first, Il telaio (The Loom) is a stinging indictment of black labour and cottage industries. The second, Il funerale del padrone (The Funeral of the Boss), examines industrial accidents and closes with the grotesque proposal to kill a worker in order not to upset the accident statistics. Instead of the worker a live goat is brought on stage and a genuine professional butcher makes ready to cut its throat. But the audience protests, the tension mounts, the lights go up and a debate opens as to whether the unfortunate animal should be killed or not, that is, whether things should be done properly instead of just being talked about. And so the audience is drawn into direct contact with the real.

Apart from their technical innovations, these one-acts are interesting for their criticism, from a left-wing point of view, of the PCI, which is accused of collusion with the bourgeoisie and reminded of its radical revolutionary duties at exactly the moment when it was widening its power-base towards the centre and evolving the concept of the national path to socialism. The other show to do the ARCI circuit in the same season, L'operaio conosce 300 parole, il padrone 1000: Fer questo lui è il padrone (The Worker Knows 300 Words, the Boss Knows 1000: That's Why He is the Boss) decisively underlined Fo's political extremism. The central theme here is the utter indispensability of culture to the proletarian struggle. This discovery is made by a group of workmen dismantling the library in a casa del popolo, as they linger over passages from Mao, Gramsci, the Gospels and Majakovsky. Reading yields to discussion and they decide to replace the books instead of throwing them away. The overall impression is somewhat confused, due to the variety of settings, in place and time, and the ambiguity of the registers employed. What do emerge clearly, however, are Fo's increasingly Maoist views - views not easily tolerated by the PCI. Italy at the time was undergoing a number of crises: the bombing in Piazza Fontana, the expulsion of the far-left Manifesto group from the PCI, the proliferation of extra-parliamentary groups on the left and right. daily confrontation in factories, universities and schools, and commotion in the streets. In this period of 'contestation' the audiences in the case del popolo and camere del lauoro (district headquarters of the left-wing Trades Union Confederation), who would normally follow an orthodox PCI line, interested Fo less than a new public of militant workers and, mainly, students with intensely critical, if not provocative, views. Daggers were out between Fo and the PCI (not to mention part of the 'Nuova Scena' group):

are texts reconstituted entirely out of suggestions found in ancient chronicles, like the story of Boniface VIII, or taken from the Gospels, like The Wedding at Cana and The Raising of Lazarus. The protagonists of these pieces are always the oppressed - the villein, the jester, even Christ - struggling against the arrogance of power. There is also the heretic seen as revolutionary - establishing alternative communities and Iiving his faith as a social as well as a spiritual revolution, until he is exterminated. Using the formulae of the commedia dell'arte, each story juxaposes the two characteristic themes of popular culture: on one hand the gross realities of physical life, and on the other the primitive popular spirituality and its perennial obsession with social justice. On stage Fo breathes life into this mass of material using a specially developed Lombardo-Venetian idiolect. Its low register and archaic flavour contrast with the literary language of bourgeois theatre and with the insinuatingly paternalistic use of dialectal forms, especially Roman, much encouraged by the mass media. In any case the meaningfulness of the spoken word counts far less than that of gesture, which Fo's performances invest with an all-pervasive power of suggestion. Grammelot and pantomime become increasingly the principal media of communication with the public.

How does Fo prevent his extraordinary talent for mime from becoming a dazzling end in itself? How does he prevent the political message from being relegated to the background? Mistero buffo operates in two registers. One is that of contemporary reality, which Fo alludes to in his commentary, in Italian, on slides showing his mediaeval characters. The second register - his Lombardo-Venetian 'dialect' - is used for the actual stories. Fo's aim is to exploit his virtuoso ability to pass from one register to another - to interrupt the performance to respond to the audience or to discuss some contemporary issue and then to slip imperceptibly back into the recitation. Thus he hopes to guide his audience by acting as a spectator of his own creations. By estranging himself from his dramatic selves he sets an example. But this chameleon ability to shift from past to present, from register to register, becomes itself a spectacle. The danger is then that the magical attraction of his solitary presence on the stage distracts the spectators from the lesson Fo wishes to impart. It is as if for dramatic theatre he substitutes epic theatre and ends up producing a variety of the bourgeois theatre that he has repudiated. To be sure, Brechtian theory proposes to avoid the danger of catharsis by employing, among other things, the grotesque register, but the very foundations of the production of popular culture had changed irreversibly by the 1960s and 1970s, and it is not impertinent, I think, to ask whether this use of the grotesque in the theatrical praxis of the time does not lead to a trivialization of content. We will come back to this later. For the moment it is enough to suggest that there was something counter-productive in Fo's efforts, partly because he was a victim of his own myth, partly because his audiences were neither those of Brecht nor those of the piazzas of mediaeval Italy.

Fo put together two other productions in this period. Legami pure che tanto io spacco tutto lo stesso (Tie Me Down as Much as You Like, I'll Still Smash Everything Just the Same) consists of two one-act plays on the theme of the exploitation of the workers. The first, Il telaio (The Loom) is a stinging indictment of black labour and cottage industries. The second, Il funerale del padrone (The Funeral of the Boss), examines industrial accidents and closes with the grotesque proposal to kill a worker in order not to upset the accident statistics. Instead of the worker a live goat is brought on stage and a genuine professional butcher makes ready to cut its throat. But the audience protests, the tension mounts, the lights go up and a debate opens as to whether the unfortunate animal should be killed or not, that is, whether things should be done properly instead of just being talked about. And so the audience is drawn into direct contact with the real.

Apart from their technical innovations, these one-acts are interesting for their criticism, from a left-wing point of view, of the PCI, which is accused of collusion with the bourgeoisie and reminded of its radical revolutionary duties at exactly the moment when it was widening its power-base towards the centre and evolving the concept of the national path to socialism. The other show to do the ARCI circuit in the same season, L'operaio conosce 300 parole, il padrone 1000: Fer questo lui è il padrone (The Worker Knows 300 Words, the Boss Knows 1000: That's Why He is the Boss) decisively underlined Fo's political extremism. The central theme here is the utter indispensability of culture to the proletarian struggle. This discovery is made by a group of workmen dismantling the library in a casa del popolo, as they linger over passages from Mao, Gramsci, the Gospels and Majakovsky. Reading yields to discussion and they decide to replace the books instead of throwing them away. The overall impression is somewhat confused, due to the variety of settings, in place and time, and the ambiguity of the registers employed. What do emerge clearly, however, are Fo's increasingly Maoist views - views not easily tolerated by the PCI. Italy at the time was undergoing a number of crises: the bombing in Piazza Fontana, the expulsion of the far-left Manifesto group from the PCI, the proliferation of extra-parliamentary groups on the left and right. daily confrontation in factories, universities and schools, and commotion in the streets. In this period of 'contestation' the audiences in the case del popolo and camere del lauoro (district headquarters of the left-wing Trades Union Confederation), who would normally follow an orthodox PCI line, interested Fo less than a new public of militant workers and, mainly, students with intensely critical, if not provocative, views. Daggers were out between Fo and the PCI (not to mention part of the 'Nuova Scena' group):

We wished to put our work - Fo states - at the service of the class movement. For us, however, 'at the service of' didn't mean filling a neat, prepackaged slot, being 'the artists of the left' who leave all policy-making to the Party and accept its directives and compromises. We had decided to contribute to the movement, to be present, to collaborate personally in the struggles. To be, that is, revolutionary militants. (Valentini 1977, 116)

Hence the break with the PCI and ARCI. 1970 sees the beginning Fo's most militant phase. The splintering of the 'Associazione Nuova Scena' led to the formation of the 'Collettivo Teatrale La Comune', which remained faithful to the aims of the former. In solving the urgent organizational problem of creating a network of theatres and centres separate from the bourgeois organizations and from those of the established parliamentary left, by now suspected of revisionism, the new group relied largely on the burgeoning, militant ultra-left. In this period, Fo's most successful synthesis of the, by now, urgent tension between art and politics came in Morte accidentale di un anarchico (Accidental Death of an Anarchist).

Morte accidentale cannot be understood without reference to the dramatic events of the time. On 12th December 1969, at the end of the 'hot autumn' four bombs were exploded in Rome and Milan. One, in the Banca dell'Agricoltura in Piazza Fontana, Milan, left sixteen dead and eighty-eight injured. Police investigations were directed exclusively at the extra-parliamentary left. An anarchist, Pino Pinelli, was arrested in Milan. Three days later another anarchist, Pietro Valpreda, was arrested. In the middle of the night of l6th December Pino Pinelli 'fell' from the window of the fourth-floor room in the police head-quarters where his interrogation was taking place. Despite ambiguous evidence, the police maintained that Pinelli had committed suicide and that both he and Valpreda were guilty of the Milan bombing. The media adopted this version. While the police were shelving the Pinelli papers, a counter-investigation into his death, published as La strage di stato (Massacre by the State), advanced the hypothesis that the bombings were part of a wider plot - involving police, secret services and judiciary - to isolate the working classes and to extirpate the vanguard of left-wing militants by means of police repression. There was a public outcry. The editor

of Lotta Continua - the group which had produced the book - was subjected to a protracted trial. Precisely at this juncture, when the official account of events was beginning to come under fire from a wide variety of commentators, Fo wrote and performed Morte accidentale.

The text of the play is based on the Comune group's painstaking researches into the bourgeois and alternative presses, collecting all the most improbable contradictions that had emanated from police and judiciary since the death of Pinelli. But while the consensus of public opinion - including the PCI, which sat conspicuously on the fence - was that the Pinelli affair was a disgraceful example of police mismanagement, Fo, along with the entire new left, maintained that it was an emblematic reaction of the ruling class towards the first stirrings of popular militancy. The success of Morte accidentale rests, I believe, on its ability to put across a revolutionary message while still being irresistible as theatre. The technical means of achieving this, though primarily designed to avoid the rigours of censorship, has a determining effect on the play's didactic efficacy. At the beginnirg of the play, Fo informs us that he intends to tell the story of Salsedo, an Italo-American anarchist who 'fell' from the fourteenth floor of the New York police headquarters in 1921. The account will, however, be set in contemporary Milan. This device allows Fo to present data from the Pinelli case in an allusive fashion so that the audience must decipher them itself. If on the one hand it substantiates the strage di stato thesis of the counter-investigation, the constant oscillation between history and current events also sidesteps the problem of over-topicality by stressing the historical continuity (the 1920s in America and the 1960s in Italy) of capitalist repression and class struggle. The outcome makes for remarkably didactic theatre - of a Brechtian inspiration - resting on the solid foundation of Fo's artistic experience, especially bourgeois farces like Isabella and La colpa è sempre del diavolo. The farcical register also harks back to these last named; the protagonist of Morte accidentale is neither Salsedo nor Pinelli, but a madman of hallucinatory metamorphic abilities. Fo transmutes tragedy into farce: this triumph of the popular-grotesque in its most extreme form expunges the last trace of pathos and the last possibilities of catharsis. In fact, it is the madman himself, under arrest for the latest of his interminable fraudulent impersonations, who has the idea of conducting a counter-investigation into the death of the anarchist. The interrogation room happens to be that of the defenestration. One after another, the madman assumes a series of socially significant roles - psychiatrist, judge, forensic investigator, bishop - hyperbolic incarnations of power in its academic, judicial and clerical guises. Via innumerable coups de théâtre and grotesque gags, the truth of the Pinelli case is slowly revealed with all its ramifications and obscure interconnections - until the madman himself is unmasked. At that point he plunges his hand into the enormous bag from which he has been pulling out the props required by his incredible metamorphoses throughout the play, and produces a bomb. He threatens to blow everybody up and is thus allowed to escape. He takes with him a tape-recording of the entire proceedings which he will send to politicians and the papers.

Morte accidentale cannot be understood without reference to the dramatic events of the time. On 12th December 1969, at the end of the 'hot autumn' four bombs were exploded in Rome and Milan. One, in the Banca dell'Agricoltura in Piazza Fontana, Milan, left sixteen dead and eighty-eight injured. Police investigations were directed exclusively at the extra-parliamentary left. An anarchist, Pino Pinelli, was arrested in Milan. Three days later another anarchist, Pietro Valpreda, was arrested. In the middle of the night of l6th December Pino Pinelli 'fell' from the window of the fourth-floor room in the police head-quarters where his interrogation was taking place. Despite ambiguous evidence, the police maintained that Pinelli had committed suicide and that both he and Valpreda were guilty of the Milan bombing. The media adopted this version. While the police were shelving the Pinelli papers, a counter-investigation into his death, published as La strage di stato (Massacre by the State), advanced the hypothesis that the bombings were part of a wider plot - involving police, secret services and judiciary - to isolate the working classes and to extirpate the vanguard of left-wing militants by means of police repression. There was a public outcry. The editor

of Lotta Continua - the group which had produced the book - was subjected to a protracted trial. Precisely at this juncture, when the official account of events was beginning to come under fire from a wide variety of commentators, Fo wrote and performed Morte accidentale.

The text of the play is based on the Comune group's painstaking researches into the bourgeois and alternative presses, collecting all the most improbable contradictions that had emanated from police and judiciary since the death of Pinelli. But while the consensus of public opinion - including the PCI, which sat conspicuously on the fence - was that the Pinelli affair was a disgraceful example of police mismanagement, Fo, along with the entire new left, maintained that it was an emblematic reaction of the ruling class towards the first stirrings of popular militancy. The success of Morte accidentale rests, I believe, on its ability to put across a revolutionary message while still being irresistible as theatre. The technical means of achieving this, though primarily designed to avoid the rigours of censorship, has a determining effect on the play's didactic efficacy. At the beginnirg of the play, Fo informs us that he intends to tell the story of Salsedo, an Italo-American anarchist who 'fell' from the fourteenth floor of the New York police headquarters in 1921. The account will, however, be set in contemporary Milan. This device allows Fo to present data from the Pinelli case in an allusive fashion so that the audience must decipher them itself. If on the one hand it substantiates the strage di stato thesis of the counter-investigation, the constant oscillation between history and current events also sidesteps the problem of over-topicality by stressing the historical continuity (the 1920s in America and the 1960s in Italy) of capitalist repression and class struggle. The outcome makes for remarkably didactic theatre - of a Brechtian inspiration - resting on the solid foundation of Fo's artistic experience, especially bourgeois farces like Isabella and La colpa è sempre del diavolo. The farcical register also harks back to these last named; the protagonist of Morte accidentale is neither Salsedo nor Pinelli, but a madman of hallucinatory metamorphic abilities. Fo transmutes tragedy into farce: this triumph of the popular-grotesque in its most extreme form expunges the last trace of pathos and the last possibilities of catharsis. In fact, it is the madman himself, under arrest for the latest of his interminable fraudulent impersonations, who has the idea of conducting a counter-investigation into the death of the anarchist. The interrogation room happens to be that of the defenestration. One after another, the madman assumes a series of socially significant roles - psychiatrist, judge, forensic investigator, bishop - hyperbolic incarnations of power in its academic, judicial and clerical guises. Via innumerable coups de théâtre and grotesque gags, the truth of the Pinelli case is slowly revealed with all its ramifications and obscure interconnections - until the madman himself is unmasked. At that point he plunges his hand into the enormous bag from which he has been pulling out the props required by his incredible metamorphoses throughout the play, and produces a bomb. He threatens to blow everybody up and is thus allowed to escape. He takes with him a tape-recording of the entire proceedings which he will send to politicians and the papers.